February 2011 Archives

Which morning brushes with soft, golden wings.

Thought has bequeathed rare legacies to bless

The mind, with all its rich imaginings.

The Book, and Shakespeare, prince of literature,

A Rollin, a Miscellany, and lo,

Biography, and Gibbon's Rome demure,

With Shelley, Byron, Tennyson, and Poe.

Euripides' Medea, Hippolytus,

Alcestis, Hecuba, with backs that shine,

The Odyssey, Virgil's Aneidos,

Homer and Horace, in a classic line.

Plutarch and Tacitus, in scarlet chrome,

Elbow Longfellow. Dante, Burns, and Keats.

Scott gravely peers from out each bulky tome,

While Browning keeps a niche for Brooke and Yeats.

Mitchell's Australia, Adam Smith, between

The Histories, Pierre Loti's tales, and Wells,

Carlyle and Omar Khayyam together lean

On Kendall, Lawson, with their bushland spells.

When evening comes, and light is chastely dimmed,

These gentle hermit spirits seem to steal

Like sentient beings 'gainst the long Past limned.

Who galaxies of jewelled truths reveal.

Arcadia is here, amid the flowers

Of literature that gem blue, purling streams,

And emerald vales, where rosy footed hours

Lead Contemplation wrapped in opal dreams.

First published in The Brisbane Courier, 12 February 1927

The mother of Henry Lawson had embarked upon her career as a social reformer as early as 1883, when she arrived in Sydney with her four children, Henry, Charles, Peter, and Gertrude. She made her first appearance in the public eye when she appealed for funds for the purpose of erecting a memorial pedestal to surmount the last resting-place of the poet, Henry Kendall.

When Mrs Lawson and her four children left their selection at Eurunderee, near Mudgee (New South Wales) to live in Sydney, her husband, Peter Larsen, remained in the country. He at that period, was a small contractor, and worked at various centres. He died at Mount Victoria (New South Wales) at the age of 55 years, on December 31, 1888, and was buried in the historic Mount York Cemetery, down the old Cox Pass-road.

Louisa was the second daughter in a family of ten girls and two boys. She was born at Guntawang Station, near Gulgong (New South Wales) on February 17, 1848. Her father, Henry Albury, hailed from Kent, in England, and her mother, Harriet Winn, was a Devonshire-born girl. The founder of the Alburys in Australia was John Albury, who, with his wife, Ann Albury (nee Ann Ralph) and a family of English-born children, arrived in New South Wales by the Woodbridge in 1838. Ann Albury is Henry Lawson's alleged gypsy ancestress. That she never possessed a drop of gypsy blood is stated by present-day members of the Lawson family. The Alburys settled on a farm at Luddenham (New South Wales), and later removed to the vicinity of Winbourne, the George Cox property at Mulgoa (New South Wales). Here it was that the son, Henry Albury, became acquainted with Harriet Winn, a needlewoman who was employed at Winbourne. Those who have read the two diverting and interesting lengthy chapters of Henry Lawson's "Grandfather's Courtship" will obtain a humorous picture of the foibles of Henry's great aunts and uncles, and will capture some of the spirit of the Nepean pioneers.POETIC AND PSYCHIC INTERESTS.

Henry Albury and Harriet Winn were married by the Rev. T. C. Makinson, at St. Thomas's Church, Mulgoa, on February 4, 1845. The pioneer Alburys, after some of their numerous family, including Henry, had married and acquired farms of their own, went to live, firstly with one of their daughters, Mrs. Mercy Sheather, at Bolwarra, near West Maitland, New South Wales and finally settled at Cundletown, on the Manning River, New South Wales. Mrs Ann Albury died at Oxley Island, New South Wales, on October 28, 1860, aged 66 years; her husband John passed away at the same farm on June 18, 1868, aged 75 years. Both are buried in the Methodist portion of the Dawson cemtery at Cundletown. Henry Albury and Harriet Winn soon after their marriage accompanied pastoralist George Henry Cox over the Blue Mountains, Albury being employed by Mr Cox as a teamster. The second daughter of the marriage, who was called Louisa, as a girl showed traits of an independent nature coupled with an intense love of the bush. Those interested will get an insight into this period of the life of Henry Lawson's mother by reading her poems "Sunset," 'The Squatter's Wife," and "A Dream."

In later years, Mrs. Louisa Lawson was keenly interested in all matters pertaining to the psychic and its unravelling, and sought inspiration from what she called the Higher Source. I am inclined to classify her as a Christian Spiritualist from the purely theological point of view.

Louisa Albury was married to Peter Larsen, a Norwegian sailor, at the Methodist parsonage, Mudgee, when but 18 years of age, on July 7, 1866, the officiating minister being the Rev. J. G. Turner. Peter Larsen took his girl-wife with him to the Weddin Goldfield at Grenfell, New South Wales, almost immediately after the union. It was there that their famous son Henry Lawson (Anglicised from Larsen) was born on June 17, 1867.

Although I knew her well in the 'nineties and in the early part of the century, I also came into closer contact with her during the twilight of her career. I, and some literary friends, used to visit her at the "little stone cottage" at Tempe, a suburb of Sydney, where she spent the last years of her life, residing there alone with her son, Charles. The "little stone cottage" was purchased by Mrs. Lawson in 1896, and her printing press removed thither. It was there that at least two of Mrs. Lawson's books of verse were published, and it was there, also, that Henry Lawson's first book of verse was printed in 1896.

FOUNDING OF "THE DAWN."

In order to give wider publicity to her aims, she founded "The Dawn" in May, 1888, and this sparkling little journal was issued regularly until 1903. Mrs. Lawson was no armchair propagandist. She knew from personal investigations the conditions under which women worked in the factories, and had also made a close study of housing and hygienic problems.

Apart from her ability as a platform speaker she could wield an able pen. Besides "The Lonely Crossing," she published a small booklet, "Dert and Do," the title being a play on the names of her daughter Gertrude and Joe Falconer, who was the original of Henry Lawson's "Joe Wilson and His Mates." But those interested in the life story of Mrs. Louisa Lawson will find her best work in the volumes of "The Dawn"--and how she loved those volumes as her friends can testify--the only known set in existence being in the Mitchell Library, Sydney. This was Mrs. Lawson's own personal set.

She died on August 12, 1920, at the age of 72 years, and is buried with her father and mother in the family grave in the old portion of the Church of England section at Rookwood Cemetery, Sydney. Her death only occurred some two years previously to that of her illustrious son.

First published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 March 1932[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Front entrance to the State Library of Victoria showing the banners for "Look! The Art of Australian Picture Books" exhibition. This runs until 29th May 2011.

"E.W.D." : Re origin of the word "Matilda" as applied to a swag. There is a reference under heading "Waltzing Matilda," "Red Page" for July 17th, 1897. "Matilda" is a typical name for the fair sex in comic songs (and one might add, farces and stage-plays), and was applied to the swag through some lonely bushman's association of the same with the female partner he longs for. (Compare the bolster called a " Dutch wife.") Some bushies rig up their swags to look like dummy females, with tied-in neck and waist, "Waltzing" became an easy addition from the idea of continued going round a circle of stations -- and so on.

First published in The Bulletin, 28 April 1904

The Flesheaters by David Ireland, 1972

Cover illustration by Brett Colquhuon

Penguin edition, 1980

My soul with soothing flatteries.

Praise with my living clay agrees.

'Tis sweet, I vow.

Give me kind words while I can feel

The modest blushes gently steal,

What time my virtues you reveal.

Oh, praise me now!

For, when the vital spark has fled,

No matter what kind words are said,

I'll simply go on being dead

And take no heed.

Or if, perchance, beneath the clay,

I hear some kindly critic say,

"He was a boshter'in his day!"

'Twere hard indeed.

'Twere bitter hard to be confined,

Gagged by grim Death, while fellows kind

Call my good qualities to mind,

And softly sigh.

I vow I'd writhe within my bier,

And strive to croak at least, "Hear, hear!"

For I have ever prized that dear

Right to reply.

And, when at last I meet my doom

And moulder in the chilly tomb,

Gaunt Death might play within the gloom --

Who knows what pranks.

My very skeleton would squirm

To hear, on my behalf, some worm

Or some unlettered grave-yard germ

Returning thanks.

Then, if you're keen on praising me,

I'd rather be alive to see

And hear and feel the flattery,

And know 'tis true.

And when I rise to make reply

I fain would droop a modest eye

And by my halting, speech imply

It is my due.

I do not want a monument.

Why should good money so be spent?

Nay, put it out at ten per cent.,

And when you save

Enough to purchase goodly fare,

Then spread me out a banquet rare.

No gift's appreciated there,

Within the grave.

Oh, praise me now while I am here;

In my attentive living ear

Pour adulation; never fear

I mind the row.

I love to hear you harp upon

Those dulcet strings. Play on, play on!

Do not delay until I'm gone.

But praise me now!

First published in The Bulletin, 31 December 1914

Update: I've fixed an error in this piece, thanks to Melva from Canberra for picking it up.

An additional piece of information in The Age article above states that Temple's earlier novel, The Broken Shore, is being developed as a three-part television mini-series for the ABC by the same people who produced Rake earlier this year. Previous mentions of this have only related to a feature film production.

That the memory of Barcroft Henry Boake is kept alive by the output of little over a year's work is in itself a testimony to the man and to his verses. What might have come from his pen had not fate intervened at the early age of twenty-six, it is difficult to say, but in the volume entitled 'Where the Dead Men Lie' (Angus and Robertson, Sydney) are thirty-one poems that have secured for their author an assured place in the annals of Australian literature.

Barcroft Boake was born at Balmain, Sydney, on March 26, 1866. His mother was the daughter of an Adelaide accountant. Barcroft Boake, sen., came from Ireland at the age of twenty and early became interested in photography, which served him throughout his lifetime as a profitable means of livelihood. When the boy, 'Bartie,' as he was called, was nine years old, an intimate friend of the family Mr Allen Hughap, took a great fancy to the lad and persuaded his parents to allow Barcroft to accompany him to Noumea, New Caledonia. Here the boy stayed for two years, learning a fair smattering of French during that time.

In 1879 Mrs. Boake died, leaving behind her nine children. Barcroft wrote to his friend Hughap at the time: "Mamma has been taken away, leaving a little baby boy behind. What an exchange!" Still life went smoothly enough for the young poet. His father's photographic business was prospering and he was in a position to give his son a good general education. He went to school until he was seventeen, spending a few months at the Sydney Grammar School and five years under a private tutor. At that time we are told "he displayed no unusual ability; was a quiet reserved boy, yet by no means mopish; fond of reading: noticeably honorable, generous and constant in his affections."

He then entered the office of a Sydney land surveyor, and for twelve months was a temporary draughtsman in the Survey Office. In July, 1886, he secured the position of field assistant to Mr. E. Commins, a surveyor whose headquarters were at Rocklands Farm, near Adaminaby, New South Wales. For two years Boake was happy in his new surroundings. Here was something novel and interesting, differing greatly from the monotony of Sydney life.

It was while at this farm that he had a most unusual experience. Barcroft was in the kitchen with a friend, Boydie, a girl, and Ted, the farm rouseabout. In a moment of practical joking, it was suggested that they should hang themselves. Boydie merely knotted a handkerchief about his neck, but the impetuous Boake climbed to the rafters, from which hung a rope used for suspending sheep. Tying his handkerchief over his face, he placed the noose (a slip-knot) about his neck. For a time he supported his weight with his hands above his head, but his strength giving out, they slipped to his sides, and he hung there a few minutes gradually lapsing into unconsciousness. Not until nearly too late did the others realise the seriousness of his position. Frantically they cut his body down, and thus Barcroft Henry Boake was saved from a fate to which only a few years later his melancholy drove him. ln a letter to his father at the time he gives a very curious account of his mental experiences while life receded slowly from him, and these were later published in a more polished form in the "Bulletin."

"I no longer possessed a body," he wrote. "Nothing was left of me but my head, and that reposed in the centre of a vast cycloramic enclosure whose walls, inscribed with the names and signs of the various arts and sciences, spun round with a waving, snakelike motion that made my eyes throb with a violent pain." For a while he thought of the futility of life, the pettiness of man. Then he felt himself sink ing, until he was lying on a ferry boat in the harbour. There had been a crash. Men were struggling, women shrieking . . and then his eyes opened to the reality of his position on the floor of the farm kitchen.

By the end of 1888 Boake had yielded completely to the spell of the bush, and left his surveying to become a boundary rider at Mullah Station. While work was plentiful he was happy, but when droving jobs were scarce or offered not enough employment to keep body and soul busy, he was wont to lapse into melancholy and brood.

"I think it is a natural consequence of being face to face with nature so continually," he wrote to his father; "but the great mystery of human nature often comes before me as I ride about. It seems to me so sad and so disheartening ... to toil with the knowledge of the vanity of it all in our hearts. Civilisation is a dead failure; it only brings these truths more forcibly before us; a savage never thinks of such things."

Still there were moments of intense joy. He was experiencing those rich, luxuriant impressions which were later to speak in his verses. He is always the keen rider, the lover of the out-of-doors, and nothing delights him more than to tell of the cattle hunt.

In a letter to his father, dated November, 1889, he mentions having obtained for the first time a full copy of the verses of Adam Lindsay Gordon. For some years, Boake had been an admirer of Gordon, and when later he commenced writing himself he was dubbed "the modern Gordon"! One day his friend, L. C. Raymond, said laughingly: 'You know, if you want to be a second Gordon you must complete the business properly and finish up by committing suicide.' Boake's only reply was a soft, quiet laugh.

In 1800 his droving brought him to Bathurst, and he seized the opportunity of visiting his father for a few days. On his return to Bathurst he discovered that his partner had drunk both his own and Boake's cheque and disappeared. This and his father's urgings persuaded him to take up surveying once again, this time with W. A. Lipscomb in the Riverina. It was during this brief period that Boake turned to verse as a medium of self-expression. "He usually wrote his verses," says Raymond, "on any odd scraps of paper and copied them carefully in a MS. Book, after which they were generally rewritten and handed to me to punctuate before being sent for publication." Acceptance by the "Bulletin" of some of his verse moved him to high spirits, but his was a nature of extremes. He was up one day and down the next.

In Dec 1981 his appointment with Lipscomb ended, and unheralded he appeared upon his father's threshold. Unwelcomed, too, it would appear, for Boake, sen. was at the time depressed over financial embarrassment, and did not want his son's melancholia to join the general pessimism. For five months he remained with his father, the latter end of the stay being irksome to a degree. His father insolvent, his grandmother confined to her bed, himself unable to obtain employment. Boake's spirits sank lower and lower. On May 2 he left the house never to return. Eight days later his body was found suspended by the lash of his stockwhip from a tree on the shore of Long Bay, one of the arms of Middle Harbour.

Of his verse, the most striking is "Where the Dead Men Lie." It has strength and power of its own, tracing the farflung burial places of the pioneers of the continent, and ending somewhat bitterly:

Moncygrub as he sips his claret,

Looks with complacent eye

Down at his watch-chain, eighteen carat--

There in his club, hard by:

Recks not that every link is stamped with

Names of the men whose limbs are cramped with

Too long lying in grave mould, camped with

Death, where the dead men lie!

In his "Song From a Sandhill," he gives a unique impression of a rainy day:--

Drip, drp, drip! They must be shearing on high,

Can't you see the snowy fleeces that are rolling, rolling by?

How many bales, I wonder, are they branding to the clip?

P'raps the Boss is keeping tally with this drip, drip, drip!

But the real Boake is found in his long, racy, galloping verses, reminiscent of Gordon (he has been called Gordon's poetic son!) In these he has preserved all the thrill of his droving days:

Thud of hoofs! thud of hearts! breath of man! breath of beast!

With Melvor in front and the rest hell to flank

So we rode in a bunch down a steep river bank.

Churning up the black tide in the shallows like yeast.

First published in The West Australian, 14 December 1929

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

First published in The Bulletin, 28 February 1918

Victor James William Patrick Daley was born September 5, 1858, in Navan, County Meath, Ireland, a seat and centre of romance. His father, a soldier, was altogether Celtic - his mother a Morrison of Scottish descent. In after years Daley used to say, "We were always poor and improvident."

Daley's knowledge of Irish legend later charged his verse with "the melancholy regret of the Celt for vanished and remote glories." When he was an infant his father died. He went to live with his grandparents, ardent Fenians, and young Victor often moulded bullets for the cause.

When Daley was 14 his mother remarried, and the family moved to Devonport, England. Here he attended the Christian Brothers' school, and in its library steeped himself in English verse.

At 16 he became a clerk in the Great Western Railway Company's office at Plymouth, but soon grew restless. His stepfather had relatives in Adelaide, and Daley set out for Australia.

Early in 1878 he landed in Sydney, where he was forced at once to take a job as gardener to a clergyman, although he knew nothing of gardening. This soon became apparent to the clergyman, so Daley went to Adelaide and got a job as correspondence clerk.

He submitted verse to a local paper with fair success, but soon he lost his clerkship. In error he sent a valued client a love lyric instead of a business letter, and was again out of work. He decided to go to New Caledonia, via Melbourne. Arriving in Melbourne, he went to the races to raise the rest of his fare. He lost his all. For a time he wrote racing notes for the Carlton Advertiser. Soon he was taken on the staff, and began writing leaders and verses. His sunny nature, soon brought him scores of acquaintances.

Then, with the musician, Charles Wesley Caddy, Daley set out for Queanbeyan, from where an acquaintance had struck it rich. On their arrival the friend had gone, and Daley became editor of the Queanbeyan Times for five or six months. He then moved to Sydney, writing for the Bulletin and Punch.

In 1888 he came to Melbourne and freelanced for Melbourne and Sydney papers. In 1898 he returned to Sydney, where his first book of verse, At Dawn and Dusk was published.

His health began to fail. In 1902, in the hope that the trip would do him good, he went -- at last - -to New Caledonia. The trip was not a success. He went to Orange, was lonely there, and returned to Sydney, where he died, December 29, 1905. He was buried next day in the Waverley Cemetery near by to the poets Kendall and Deniehy. He left a wife and four children.

Perhaps Bertram Stevens' words are the finest summing up of Daley: "Light-hearted, brave, generous, but weak of will -- the man was finer than his work, and his work is good." H. M. Green, in his An Outline of Australian Literature, writes: "Poetry was the one fixed star in Daley's life. He not only had far more craftsmanship than any of the balladists, but in his blood were that love of words for their own sake, love of sound and imagery, which help to distinguish the poet from the mere versifier. No Australian before him had created so many fine images."

First published in The Argus, 28 October 1944

[Thanks to the National Library of

Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Author reference sites: Austlit, Australian Dictionary of Biography

See also.

The Chantic Bird by David Ireland, 1968

Cover illustration by Robin Mundie

Sirius edition 1979

The shortlisted works in both categories for the South Each Asia and Pacific region are:

Best Book

Reading Madame Bovary by Amanda Lohrey (Australia)

That Deadman Dance by Kim Scott (Australia)

Time's Long Ruin by Stephen Orr (Australia)

Hand Me Down World by Lloyd Jones (New Zealand)

Notorious by Roberta Lowing (Australia)

Gifted by Patrick Evans (New Zealand)

Best First Book

21 Immortals by Rozlan Mohd Noor (Malaysia)

A Man Melting by Craig Cliff (New Zealand)

The Graphologist's Apprentice by Whiti Hereaka (New Zealand)

The Body in the Clouds by Ashley Hay (Australia)

Traitor by Stephen Daisley (Australia/New Zealand)

A Few Right Thinking Men by Sulari Gentill (Australia)

Last year's winners in the region were: Best Book - The Adventures of Vela by Albert Wendt (Samoa) and Best First Book - Siddon Rock by Glenda Guest (Australia).

Jonathan Strahan's Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year is now up to volume five and features the following Australian stories:

"Under the Moons of Venus," Damien Broderick

"The Miracle Aquilina," Margo Lanagan

From what I can figure Rich Horton started his series of "Best of..." volumes in 2006, producing one book for each of science fiction and fantasy. The past two years he has combined both into one. His The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2011 acually covers 2010 and includes:

"Under the Moons of Venus" by Damien Broderick

With rainbow eyes of feathers made;

For me no ostrich feather fan

Plumes o'er a throne of fine brocade;

No coffee-coloured slaves kneel down

Abased to earth beneath my frown!

No marble palaces are mine,

Pale mirrored in the lotus lake.

No elephant, coin-bonneted

Carries a howdah for my sake,

With painted head and gilded feet,

His trunk in champak blossoms sweet.

I boast no chests of jewels locked

In secret caverns for my own,

No gold Egyptian beds that lie

Beneath where Horus wings in stone.

No alabaster jars are mine

From which the Pharaohs poured their wine.

And, yet, I have a magic wand!

Hey! Presto! And such scenes leap up.

A Sleeping Beauty in a wood;

The Seneschal sprawls o'er his cup;

The hound lies with the hunted hare;

The hawk hangs frozen in the air!

Out of the dust of countless years

I can bring back proud Egypt's Queen,

Out of green Arden's mossy dells

Can conjure you a bunting scene,

Or, if austerer fancy wills,

Some Buddhist temple from the hills.

Bring me a penny pot of ink,

A wooden holder and a nib,

And I will show you wizardry

To which some ancient mage was sib.

A sheet of paper to my band

-- What is it, sires, that you command?

First published in The Courier-Mail, 21 July 1934

E. J. Brady, who died this week at 82, was one of the lost links with the days when the world was wide -- with the romantic, hopeful, acutely nationalistic Australia of the nineties, when Australian art, literature, and politics all had a flowering, never since repeated.

They were days of low living standards but high hearts. Out of the turmoil, industrial and social, Australians believed, would come a new Australia.

Round about the turn of the century we had all that is most notable in our life.

Broadly, our art was born with Roberts, Streeton, Conder, Mccubbin, and the rest; our literature with Lawson and Tom Collins, Paterson, Daley, Barbara Baynton; our political cast of thought with the Lanes, Brady, and their friends.

After that came a long period of nothing. The creative artists died, or went away, or lost their inspiration. The politicians, in many cases, renounced the visions of their youth, or lapsed into disillusion.

A few people like Brady remained as visible and vocal reminders of the spacious days, carrying with them always a sort of grandeur out of the past, a bigness, making us aware of something lost in our life.

Brady was a roamer in accord with the spirit of his time. As a boy he had gone to North America.

"I crossed it from Frisco to Washington, D.C.," he wrote to me years later, "when the cowboys were still bringing their herds up from Texas.

"The Old Man saw them with me, spreading over the Western plains, 20 years after he had seen the same plains covered with buffalo.

"In my time out West the train sweepers carried two guns slung low and bowie knives in their boots."

Back in Australia, Brady went to school again with Rod. Quinn and George Taylor, author of that delightful book of reminiscence "Those Were The Days."

A clerk in a wool store for a time, he was precipitated into the emerging Labor movement, when, on refusing to become a special constable in the great maritime strike, he was immediately sacked.

He became a "wild leader" of the strike, and at 22 he was editor of the "laborer's Bible," the "Australian Workman" weekly newspaper.

One day Lawson appeared at the "Workman" office; it was a sufficiently important occasion to adjourn for refreshment, leaving the office boy (afterwards Sir Frank Fox) in charge.

With long-sleevers of colonial beer at threepence a go, Brady and Henry discussed the Australian Republic; for those were the days when, in Brady's own words, they dreamed of "the establishment of a new Hellenic democracy."

Brady had a quaint and typical story about Lawson, incidentally. (Brady always had his feet on the ground, but Lawson was naive and childlike in many matters.)

Twenty years or more after the "Australian Workman" days the old friends had a reunion.

"You - old sinner, you ought to have been dead long ago!" Brady said.

"Why? Why did you think that?" asked Lawson.

"The way you knock yourself about."

Lawson pretended to think it over carefully.

"Beer saved my life," he said at last in a voice of simple conviction.

"Beer?"

"Yeth, Ted - Beer."

And he added, after a further reflective pause, "If I'd been drinking hard tack I WOULD have been dead long ago."

The unhappy warrior

In the nineties, Brady roomed with Ernest Lane (still happily flourishing in Queensland), brother of William Lane, of New Australia celebrity.

But the inevitable fissions and disillusionments of radical parties occurred, and Brady gave practical politics away.

At heart he was unchanged.

After half a lifetime the old fires stirred in him. He wrote to his old mate Lane, "With armor dinted by many blows, bearing the marks of countless wounds, you are crying your warcry still, while a sardonic philosophy has led men like myself to nowhere in particular."

Round about this time Brady decided to return to Melbourne to see whether it was possible to kindle in others the visionary fires of the nineties.

It wasn't.

The fate of rebels

No reasonable person would suggest that Brady was a great poet.

But Brady was a good poet, and to understand and to appreciate him and his contemporaries, whether writers, painters, or politicians, you must consider all of them together in the environment of the nineties.

Brady's first book of verse, "The Ways of Many Waters," was published in 1899 by the "Bulletin"; most of its contents had appeared in the "Bulletin" and in the Sydney "Sunday Times."

These ballads of the sea were the best things Brady ever wrote; something went out with him when the "sardonic philosophy" of which he spoke replaced the earlier passionate faith.

"Lost and Given Over" and "Down in Honolulu" are probably the best known; my own feeling is that "I've Got Bad News" is, perhaps, the best.

This is the story of a sailor who, in time of industrial depression, threatens the master with a marlin spike, and is shot dead for his act:

He laid his hand to a marlin-spike --Oh, he was a man to know!

And the deck ran red where he fell and bled,

But he shouldn't have acted so.

Here, it seems, are the beginnings of Brady's sardonic philosophy -- some rebels recant, but others who lay their hands to marlin-spikes are shot down. If they wanted to survive, in a world of injustice, they "shouldn't have acted so."

It is a general rule in Aus-tralia (the only, exception I can think of is the case of Dame Mary Gilmore) that creative writers are never honored by nation or by academic bodies whose distinctions are reserved for people who write about writing, who index it, or who collect it.

Officially, creative art of any kind is not respectable.

Brady belonged to a generation when artists, very certainly, were not respectable in the eyes of bumbledom; they were poor, they drank too much beer, and sometimes they were political rebels.

Some of them got over being rebels; some of them (such as Brady) never drank beer excessively anyway; but none of them ever got over being poor.

Men like Henry Lawson were poor because they were essentially unworldly.

Brady wasn't unworldly. He said cynically that anyone who understood Marx could play the stock market successfully -- if he could be bothered.

Dilemma of a nation

Brady's dilemma was not peculiar to him-self or to his generation. It is Australia's dilemma.

We no longer believe that the Hellenic democracy is imminent, practicable, or even possible.

We can't recapture the raptures which moved Victor Daley and his friends, or the poetic vision of the young Streeton and his friend Conder.

At the moment, officially, we don't seem to believe anything at all; unless it is that in some mysterious way we can be economically and spiritually saved by an infusion of Italians and West Germans.

Fifty years without a national vision is a long time.

It remains for us to find another.

[Books to which I have specifically referred are: "Those Were the Days," by George A. Taylor (Sydney: Tyrrell's Ltd., 1918); "Henry Lawson," by His Mates (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1931) ; "Dawn to Dusk," by E. H. Lane (Brisbane, 1939) ; and "The Ways of Many Waters" by E. J. Brady (Sydney: The Bulletin Newspaper Co. Ltd., 1899).]

First published in The Argus, 26 July 1952

[Thanks to the National Library of

Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Author reference sites: Austlit, Australian Dictionary of Biography

See also

First published in The Bulletin, 2 May 1903

Novel - Science Fiction

Zendegi - Greg Egan

Young Adult Books

Factotum - D. M. Cornish

The Keys to the Kingdom, Book 7: Lord Sunday - Garth Nix

Behemoth - Scott Westerfeld

First Novels

Clowns at Midnight - Terry Dowling

Collections

Amberjack: Tales of Fear and Wonder - Terry Dowling

Anthologies - Original

Sprawl edited by Alisa Krasnostein

Godlike Machines edited by Jonathan Strahan

Swords & Dark Magic: The New Sword and Sorcery edited by Jonathan Strahan and Lou Anders

Anthologies - Reprint

Wings of Fire edited by Jonathan Strahan and Marianne S. Jablon

Anthologies - Bests

The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year Volume Four edited by Jonathan Strahan

Art Books

The Bird King and Other Sketches - Shaun Tan

Novelettes

"A Thousand Flowers" - Margo Lanagan

"Eight Miles" - Sean McMullen

"To Hold the Bridge" - Garth Nix

Short Stories

"Under the Moons of Venus" - Damien Broderick

"The Miracle Aquilina" - Margo Lanagan

"A Suitable Present for a Sorcerous Puppet" - Garth Nix

"Brisneyland by Night" - Angela Slater

"All the Love in the World" - Cat Sparks

Note: there is a chance I've missed some.

Xavier Herbert edited by Grances de Groen and Peter Pierce, 1992

Cover design by Craig Glasson using Ron Edwards's portrait of Xavier Herbert

UQP edition 1992

And in the flowery gully at my feet

Deaf stones too dumb for summer's melody

And the long wind's compassionate, slow beat.

Rest with a book -- your book all fire and dew,

Wrought of the brown old earths eternal youth;

Light, song, and star-dream -- all the soul of you,

Guarding herein the treasury of Truth.

Sleep with a book. A dead leaf falls on me,

So Nature yields her labor to the times.

But till the quiet of eternity

Love's happy lips shall kiss to your green rhymes.

First published in The Bulletin, 8 April 1920

Dr. Karl Wolfskehl, a German author and philosopher, who recently visited Australia, described the late C. J. Brennan as one of the most interesting poets of modern times. This estimate confirms the belief of the many admirers of Chris. Brennan in the greatness of his work. As the publisher of the first edition of his poems in 1913 I have set down here some recollections of a distingushed son of New South Wales.

Christy Brennan, the poet's father, with a sound knowledge of his trade as a brewer learned with the famous firm of Guinness in Dublin, emigrated to Sydney, and soon secured a position with the Castlemaine Brewery, on the site now occupied by the new Municipal Markets, at the junction of Hay and Quay Streets. He was one of the first brewers to bottle colonial beer, in the Colonies. The firm, doubtful of the experiment, decided to call it Brennan's Beer after the name of their brewer. One of Chris Brennan's cherished heirlooms was an original label placed on the bottles.

Preferred the Classics.

Christopher Brennan, senior, married a lass from Ireland, and their son was born on November 1, 1870. They cherished the hope that the lad, a promising scholar at St. Ignatius, Riverview, would enter the priesthood and accompany Cardinal Moran to Rome to study there, and it was a great disappointment when just before the close of his college days he wrote that he felt he had no vocation for the Church. His place was taken by a contemporary, Stephen Burke, who reached a high position in his calling.

Disappointed but not dismayed, his father saw visions, so dear to Irishmen, of his son devoting his talents to the Bar, or the Parliament of his country -- but it was not to be. The call of the classics and literature was too strong, and his parents ultimately lived to see him a Professor of his University and one of the leading poets of his day.

It was at the student stage of his life that our life-long friendship commenced. When seeking for the text books required for his first year, he was not satisfied with the editions recommended by the University Professors and those of the lending English Educational Publishers. He required annotated editions from Germany and other countries. Few students acquired such a complete collection of classics for their University courses, and I can remember procuring a large edition of "Lucretius" from Germany. All these contributed to lay the foundation for some of the most beautiful classical poems in the English language. Naturally, he cast his eyes farther afield to the great seats of learning in Europe, and his efforts were eventually crowned with success when he was awarded the much-coveted James King of Irrawang Scholarship, tenable for two years abroad. He selected Germany for the continuance of his studies, which took him from his native land for two years.

A high-spirited incident of his undergraduate days nearly cost. Chris. Brennan his University career. When his father heard with horror, being unversed in the ways of under-graduates, that his son entered the lecture room with jam tins and horse shoes decorating the fringe of his University gown, he thought he would be more usefully employed at the brewery washing bottles. The experiment did not meet with the success it probably deserved. The early start at 6 a.m. had its disadvantages, and the dreamy nature of a poet caused young Chris. to wander away from his uncongenial occupation under a goods lift which came down and nearly extinguished the future poet and scholar. His father concluding that Chris. would be safer dreaming in the open spaces of the University, Chris. was back in the lecture-room the next morning. A poor bottle washer was lost to the brewery trade and a brilliant student added to the world.

Brennan had entered the University in 1888, and in his first year he gained first-class honours in Classics. In his second year he again obtained first-class honours in Classics; in his third year he obtained second-class honours in Classics, and was awarded the gold medal and first-class honours for Logic and Mental Philosophy. He graduated in 1891, and was admitted to the M.A. degree in 1892.

Among the Books.

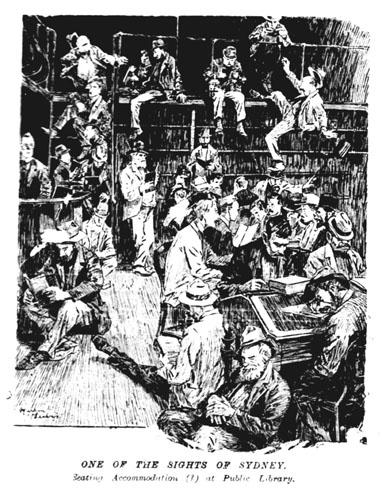

Returning from Germany with a vast knowledge of classical and modern languages, but with limited prospects for such accomplishments, Brennan secured a position as assistant librarian and cataloguer at the Free Public Library. It seemed in those days that many of his cherished hopes were to end on the rock of fiuitless endeavour, but he found compensation in the formation of a life long friendship with his two fellow assistants -- F. R. Jordan, who was to become Chief Justice and Lieutenant-Governor of New South Wales, and John Quinn, later one of the leading librarians of the Commonwealth.

The library position not being arduous Chris Brennan had time to devote himself to poetry, and later friends approached him to allow a collection of his work to be published by subscription, releasing him from all financial responsibilities. A debt of gratitude is due to the late Judge Edmunds for sponsoring the undertaking. The subscription list contained the names of some of the leading citizens of the day, including Sir George Wigram Allen, Sir Julian Salamons and Sir Joseph Abbott. Some years later the subscription list was reopened and the work was completed, but many of the subscribers had passed away. I realise to-day how I should have cherished that subscription list.

The edition when printed containted a list of some of the original subscribers, headed by Lord Noithcote and Sir Harry Rawson. Subsequently Brennan was appointed lecturer and professor of German and Comparative Literature. He was a familial figure in the leading new and second-hand bookshops, spending some of his happiest moments wandering round the bookshelves, the great attraction being the second-hand classics. All thoughts of the commercial side were lost and it was with a troubled feeling that one saw the pile of old classics gradually growing higher by his side, knowing that they augmented an already overburdened account; the only consolation being that probably the books were mostly beyond any other clients' requirements.

I persuaded him to translate some of the set authors -- Livy and others -- and write some articles for the New South Wales Teacher and Tutorial Guide, the one on "Julius Caesar" being one of the best contributions that ever appeared in the journal. He subsequently relinquished his professorship, and passed away, suddenly on October 5, 1932.

Criticism of his work I leave to others, though not without retelling a saying of Disraeli. "You know who your critics are, the man that has failed in literature and art."

First published in The Sydney Morning Herald, 3 December 1938

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Our daily ran for a month before election day, and apparently we were a great success, as W. M. Hughes had a 13,000 majority-- his publicity cost of the election being £2/15/, in 10 lots of advertising dodgers at 5/6 each. Even then, 25 years ago, Dennis, was a frail man -- or rather frail boy! Because he was always a boy. The memory of "Den" is for me the memory of courage-- of a brave thing in a weak body, living on the strength of a spirit that carried him for many years.

When I think of courage at its highest in men it is not the courage that makes for spectacle. Heinie, invalid for most of his life, singing his brave songs in exile; Carlyle the dyspeptic, stunned by the loss of the MSS of his French Revolution, saying, "I must write it better"; bedridden Henley insisting that he is the captain of his soul; Robert Louis Stevenson, marked for early death, yet writing as if he would live for ever; Victor Daley, sapped by tuberculosis, yet thinking clearly to the end and singing his songs as if he were to be on this earth immortal; all the heroes of brush and pen who have fended off their own dissolution by newly creating humour and beauty-- these are the epic men of the world.

And of them was C. J. Dennis. More terrible than active pain is the slow suffocation of disease of respiration; the recurrent sensation of impending death; the recovery only to die again a many deaths. Dennis had that experience of smothering horror daily repeated for many years, and he worked and chuckled in verse and was cheerful enough to help thousands of people-- also hopeless, but not articulate.

It is a long way back to our ha'penny paper in 1913, but in the end Clarence Dennis had not greatly changed. Painfully then, always-- his life was a battle of willing spirit and physical frailty. The part of the real writer is to ease the irritations of the reader and bring to him distraction from the working troubles of a life that is often hard and at the best is pitifully short. To the people weary of struggle the man who can deliver humour and cheerfulness is a benefactor, and, so judged, Charles Dennis deserves well of his country.

First published in The Courier-Mail, 23 June 1938

[Thanks to the National Library of Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Disturbing Element by Xavier Herbert, 1965

Cover artwork Harvest by Gail English

Flamingo edition 1987