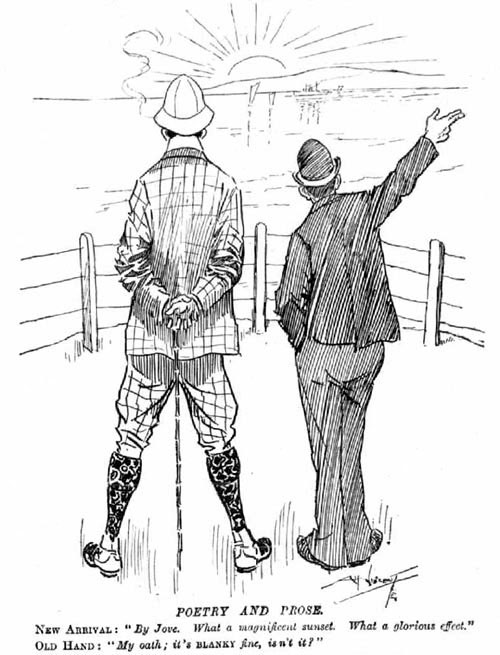

Two names generally are at once mentioned when men speak of Queensland poets -- Brunton Stephens and George Essex Evans. Both were Englishmen, and both are dead. They were close friends and mutual critics and mutual admirers. Evans, though English, was Welsh in paternal descent. He was born in London on June 18, 1863. He was educated at Haverford West and at the Channel Island of Jersey. His master in Jersey was the Rev. Mr. Le Breton, the father of the Mrs. Langtry who first was famous as a beauty and then as an actress. Essex Evans often spoke of Lily Langtry, whom he knew very well while he was at her father's school. He came to Queensland when a youth, at about 18 years of age and joined his brother John on a farm near Allora, Darling Downs. After some experience there he went away to the Gulf of Carpentaria with a survey party and found the life pleasant. The great open spaces appealed to him and the wonderful sincerity of personal relationships out there; but he had a bad accident, a broken leg which really never became sound again, though he continued as a fine athlete. He was sturdily built, and very powerful, a first-rate wrestler, a speedy runner and he represented Queensland in Rugby Union football against New South Wales. Later he as a matter rather of compulsion confined his athletics to long walks. After his experience in the Gulf country he returned to the farm at Allora, but that life was not congenial, nor was it profitable. Vainly one remonstrated and spoke of the great poet who "went singing down his corn." Essex Evans simply hated the daily round on the farm. He had thoughts of other things. "He had the impulse of the poet, not of the farmer. Those who were his intimates in later years know the story, and those who did not know Evans personally will find it in his work, as, for instance, in the poem "Out of the Silence" published in his last book:

Here in the silence cometh unto me

A song that is not mine,

With wash of waves along the cold shore line,

And sob of wind, and rain upon the sea.

In many of his even later poems are found the repercussions of his Gulf of Carpentaria days. Of these may be particularised "A Pastoral," "The Grey Road," "On the Plains" -- two poems in the one volume there are of this title -- and Essex Evans told the writer that all through his time in the North-West he felt the call of the restful wildernesses, and the lines :

Calm are the plains -- when the moon's clear beams are shed

And the wilds lie hushed, all shrouded in silver grey --

had been singing through his mind for years before he put them into form.

It was while at Allora that he first took his courage in both hands and sent some verses to the "Queenslander." Mr. Joseph Butterfield thought well of them, and they were published under the pen-name of "Christophus." The young poet continued to send his work to the "Queenslander," and soon it attracted more than notice, and at the advice of one who was a stranger then he wrote above his name. To the same adviser, in long after years, in 1906, he sent a copy of "The Secret Key, and Other Verses," inscribed "To --- who, more than 20 years ago, was the first to detect any merit in my verse and to give me encouragement, from his chum Geo. Essex Evans." The poet became a regular contributor to the "Queenslander" and "Courier" with verse, narrative poems, short sketches, and humorous stories in rhyme. Later he joined the staff of the papers and did much good work, but on being appointed to a Government office at Toowoomba he gave up Press work and devoted his spare hours to poetry and literature generally, and he promoted and edited "The Antipodean." His next work for the Government was the writing of booklets upon the State for publication by the Intelligence Bureau, and these contained many prose gems which had the heart-whole admiration of so fine a critic as the late Mr. P. J. M'Dermott, Under Secretary to the Chief Secretary's Department, who was the poet's official head. Essex Evans lived part time in Brisbane, but his home and his heart were at Toowoomba, or just down the range from the Queen City, near the old Toll Bar, and the site of "Glenbar" of his days is often pointed out to those interested in the higher things of Queensland life. The poet married a widowed daughter of the Rev. E. Eglinton, a sister of the late Mr. Ernest Eglinton, P.M., and of Mr. Dudley Eglinton, a well-known writer on scientific subjects. Mrs. Essex Evans survives, and a son, a younger Essex Evans, is a fine young fellow in the service of the National Bank of Australasia.

George Essex Evans died at Toowoomba on November 10, 1909 after an operation. His death was a shock to his family and to many friends. At Toowoomba, in Webb Park, overlooking the Range, a monument to the poet has been erected, and on it -- North, South, East and West -- are verses from his beautiful tribute to "The Mountain Queen."

THE WORK OF ESSEX EVANS

Some years ago a prize was offered at Toowoomba for the best essay or appreciation of the poems of Essex Evans. The judges were Mr Littleton Groom, now Sir Littleton, and the writer of this article. The prize was awarded to Mr. Heber Longman, now Director of the Queensland Museum and a well known writer on literary and scientific subjects. A point influencing the judges was that Mr Longman waa discriminating. One other essay was beautifully done, but it was a eulogy without discrimination. In appreciating Essex Evans's poems discrimination is necessary. Though in his earlier work there is much that is very fine and beautiful the quality is very uneven. The poet knew that. He felt, and often said so, that he was evolving, finding the correct expression and he was not by any means satisfied that he had done his best work. But even of his earlier work much was distinctive, and in the whole range of what he accomplished only one poem can be classed as under an influence. The very fine thing "A Medley" has the metre, and in places other similarities, of the "Locksley Hall " of Tennyson. The colour is Australian, but part of the philosophy is Tennysonian. One catches the environment in

Eastward in the skies of morning rosy tinges streak the gray,

Bars of crimson change to golden-glitt'ring heralds of the day,

Like a blood-red shield uprising swims the sun in palest blue,

Crowne the hills with crests of splendour, flashes on the trembling dew --

And the other spirit is in this:

He is best and he is noblest who has kept through good and ill

Something of his purer nature, something of his childhood still.

A writer in the London "Daily Telegraph," reviewing "The Secret Key and Other Verses," selected for special consideration "The Song of Gracia " This was quoted and described as standing in beauty of thought and expression with much that was best in English verse. For the benefit of those who do not know the poem the following extract is given, "torn from its context" though it be:

Two violets, seeking Paradise,

Have hid themselves within her eyes.

Her lips are roses. She doth wear

A sunbeam woven in her hair.

And of the foam-flake of the sea

Her cheek and neck and bosom be.

That is very different from the slogging style of the stirring indictment "Ode to the Philistines," from the popular "The Women of the West," and from other of the more known of the poet's work. It will perhaps interest readers to know that though Essex Evans was not a phrase-maker and had no pose in that respect he loved certain little things that he wrote. In "An Australian Symphony" he has the following :-

Could tints be deeper, skies less dim,

More soft and fair,

Dappled with milk-white clouds that swim

In faintest air?

The soft moss sleeps upon the stone,

Green scrub-vine traceries enthrone

The dead gray trunks and boulders red --

He was very fond of his line, "The soft moss sleeps upon the stone." It is certainly very beautifully expressed. It will perhaps be remembered that on the accomplishment of Federation a substantial prize was offered for the best ode on "Commonwealth Day." It was awarded to the Queensland poet, George Essex Evans. That was a great gratification to him and to his friends, and certainly his ode was a very brilliant and very stirring tiling. It opened with:

Awake! Arise! The wings of dawn

Are beating at the Gates o' Day!

The morning star hath been withdrawn,

The silver vapours meit away!

Rise royally, O Sun, and crown

The shoreward billow, streaming white,

The forelands and the mountains brown,

With crested light --

And the conclusion is very fine :

From shameless speech, and vengeful deed,

From license veiled in freedom's name,

From greed of gold and scorn of creed,

Guard thou our fame!

In stress of days that yet may be

When hope shall rest upon the sword,

In Welfare and Adversity,

Be with us, Lord!

That was written before the "Recessional" of Kipling. With an intimate knowledge of the work of George Essex Evans the writer's view is that outstanding and of greatest value is "Lux in Tenebris." On the occasion of a lecture by Mr. Henry Tardent -- a most appreciative friend of the poet -- at the rooms of the Royal Geographical Society, Sir Matthew Nathan said he considered the poem the best thing Essex Evans had done, and to the very great pleasure of the audience he recited it. The sweeter things, and the more stirring things of the post are the more popular to-day, but "Lux in Tenebris" is the best monument of George Essex Evans. And as a music lover the writer submits the following :

O Poets, round whose souls, since the beginning,

Strange echoes tremble and wild visions throng,

Ye all have heard the sweetness of the singing,

But no man knows the meaning of the song --

By the death of Essex Evans Queens- land and Australia lost a poet who accomplished much, but the full harvest of whose genius had not been gathered. The Queenslander, as we claim him, holds a high place in the estimation of the critics and all who know his work, and it reveals a very fine mind and strong masculinity, combined with culture and refinement.

First published in The Brisbane Courier, 14 October 1927

[Thanks to the National Library of

Australia's newspaper digitisation project for this piece.]

Note: you can read the full text of the Essex Evans poem, "Ode for Commonwealth Day".